Twenty years ago, on January 25 2001, a virtually unknown German supermarket chain quietly opened its first stores in Australia.

The two stores – one in Sydney’s inner-west suburb of Marrickville, the other in the outer south-west, near Bankstown Airport – were small, about a quarter the size of a mainstream supermarket. Each stocked just 900 products, 90% of which were unknown brands.

Shoppers had to bring and pack their own bags themselves. To use a trolley required a “gold coin”. They didn’t seek to entice customers with “loyalty” rewards or other gimmicks.

Few Australian supermarket executives at the time would have considered them models for success. They couldn’t imagine the impact Aldi would have on Australia’s retail sector and shopping habits.

Aldi’s history

Aldi’s story began in 1913, when Anna Albrecht opened a small grocery store in 1913 in the city of Essen, western Germany.

Her two sons, Karl and Theo, took over the business after World War II. In the impoverished conditions that followed Germany’s defeat, they focused on keeping costs, and prices, low. Among their strategies were to stock only the most popular items and avoid perishable items.

By the end of the decade they had more than a dozen stores, and by the end of the 1950s more than 300.

The brothers adopted the the name Aldi – combining the first two syllables of Albrecht Diskont (“discount” in German) – in 1961 (though accounts differ on the year).

At about the same time (again, accounts differ on the year) they had a major disagreement over whether to sell cigarettes. They resolved the dispute by splitting the business into two geographic entities: Aldi Nord (“North”), run by Theo (and selling cigarettes), and Aldi Süd (“South”), run by Karl. The split was amicable, and they managed the two divisions collaboratively.

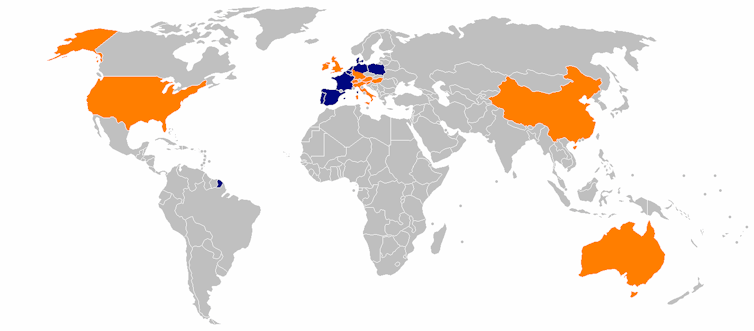

From the late 1960s Aldi began to expand across Europe, beginning with the acquisition of Austrian grocery chain Hofer. It opened its its first US store, in Iowa City, in 1976, and its first British store, in Birmingham), in 1990.

So by the time Aldi opened its first stores in Australia, it was a booming multinational. It now has more than 10,000 stores in 20 countries, including China.

Aldi’s growth in Australia

In coming to Australia, Aldi pounced on a gap in the grocery retail market.

The “food discounter” model had been dominated by now defunct Franklins and Bi-Lo (owned by Coles). By the late 1990s, however, these chains had messed with their “no-frills” model through attempts to go upmarket. It proved disastrous. Franklins went into terminal decline. Coles abandoned the Bi-Lo brand in 2006.

Aldi expanded quickly. By mid-2003 it had 38 stores in New South Wales and six in Victoria. By 2011, it had 251 stores. By early 2013, more than 280, and had expanded to Canberra.

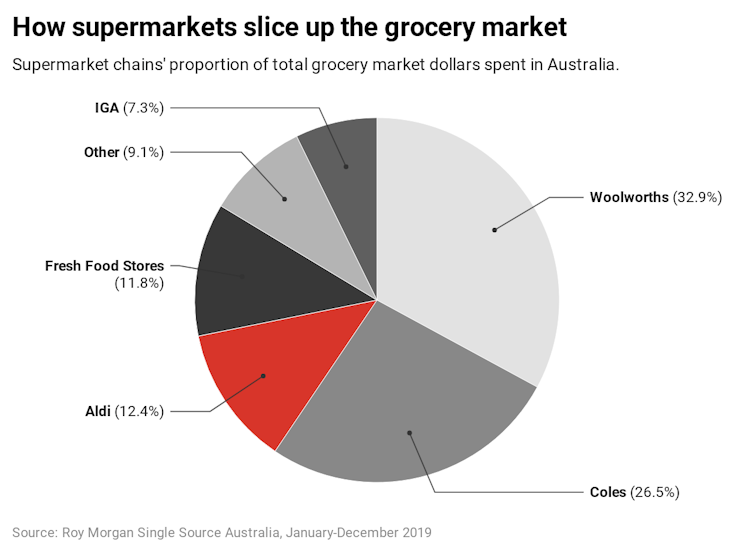

It overtook the IGA group to become the third-biggest player in Australia’s supermarket sector by the end of 2013 – taking 10.3% of all grocery dollars (with Coles having 33.5% and Woolworths 39%). Its first stores in South Australia and Western Australia came in 2016.

It now has more than 500 stores and a 12.4% share of Australia’s A$110 billion food and grocery sector (according to the most recent data from Roy Morgan).

In 2020 Aldi was named Australia’s best supermarket by consumer review website Canstar Blue (the seventh time in a decade), and second-most trusted brand (after Bunnings) by Roy Morgan.

Its practices have influenced how the other supermarkets do business. In particular it has forced competitors to increase their own “private label” (or home-brand) products, introduce “phantom brands”, and promote ever-changing “special buy” general merchandise ranges.

Private and phantom labels

In 2004 private labels comprised an estimated 9% of the products Coles and Woolworths stocked. By 2019 they made up 30% of Coles’ sales. Woolworths has similarly increased its private-label range, due explicitly to pressure from Aldi’s arrival and expansion.

Notably, Aldi sells no “ALDI” branded products. Instead it trades in phantom brands, such as “Belmont” ice cream, “Radiance” cleaning product and “Lacura” skin care. These brands are intended overcome perceptions of private label items being lower quality.

In 2016, Woolworths launched its own range of phantom brands. Coles followed suit in 2020 with brands including “Wild Tides” tuna and “KOI” toiletries.

Special buys

The bigger supermarkets have also been forced to emulate Aldi’s drawcard of bi-weekly “special buys” – heavily discounted items not normally sold in supermarkets. These have included televisions, lawn mowers, vacuum cleaners, motorcycle jackets, luggage and (curiously for a country like Australia) ski gear.

There are always limited quantities and shoppers regularly experience disappointment. Despite this – indeed because of this – shoppers will queue and keep coming back. These quirky, seasonal, limited-stock items create excitement and FOMO – fear of missing out.

In June 2020, Coles launched its own fortnightly “special buys”.

Unapologetically Aldi

While its competitors have emulated Aldi in several ways, the German chain remains a very different no-frills operation.

It hasn’t bothered with investing in the self-service checkouts that are now ubiquitous in other stores. It continues to offer only long conveyer belts and seated register operators.

Nor does Aldi have plans to facilitate online deliveries, in which the two supermarket giants have invested heavily.

It never had to cope with customer backlash over phasing out free single-use plastic bags either. Because it never offered free shopping bags, always charging 15 cents for them.

So Aldi continues to be an exception to the rule in Australian supermarket retailing. It history suggests that’s a recipe for continued success.